As a seventh grader at Stonewall Jackson Middle School, Jose Rodriguez played the trumpet in the school band and put up with constant taunting from another boy in his section.

One day Rodriguez, a transplant from Puerto Rico, tried to stand up for himself. The response was a racial slur, then a moment Rodriguez never forgets: “The trumpet case crashing to my face and me on the floor.”

He still remembers the instrument case used as a weapon — because it was decorated with a Confederate flag sticker.

Today, Rodriguez, 39, is called father and presides at the Episcopal church Iglesia Jesus de Nazaret, which sits less than 2 miles from Stonewall Jackson’s campus in east Orlando.

He wants the middle school’s name changed. So do other residents.

The name of the Confederate general, “a man who promoted oppression,” represents a “legacy of prejudice and discrimination” that doesn’t belong on a public school, Rodriguez said.

“That name hurts,” he said, and serves as a symbol that, even when he was a boy in the early 1990s, made his white antagonist feel he could bully and strike a student who, in his view, didn’t belong.

The Orange County School Board likely will take up the issue of the school’s name in early 2020.

The school is the only one in Central Florida still named for a hero of the Confederacy.

Confederate names and statutes — which some view as symbols of slavery and white supremacy but others as key slices of American history — have been the source of intense scrutiny and debate nationwide since the June 2015 shooting deaths in a black church in Charleston, S.C. The convicted killer was a white supremacist who posed for photos with a Confederate flag.

Orange’s school board voted in 2017 to change the name of Robert E. Lee Middle School to College Park Middle School.

Stonewall Jackson, which opened in 1965, was once all white but now serves a largely Hispanic population, with many of its students from families who moved here from Puerto Rico.

Stonewall Jackson’s school advisory council — a panel made up of educators, parents and community members — said last year that it wanted a new name and then this fall voted to recommend the “Stonewall” be dropped and the school be known simply as Jackson Middle.

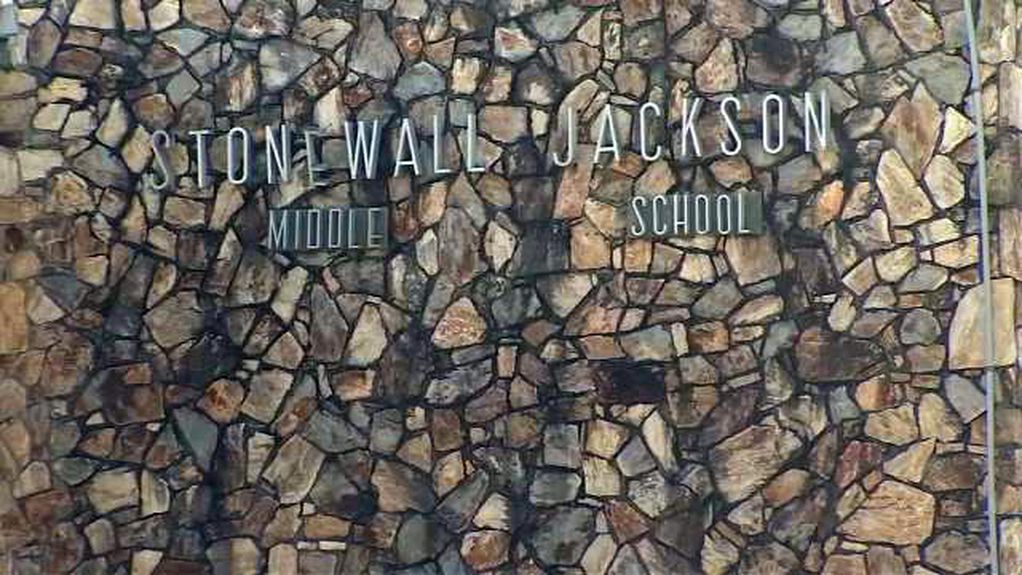

Though two signs on the school spell out its full name, the school’s website uses only Jackson, as does a newer sign on the school marquee. About a decade ago the school changed its mascot from the Raiders, a reference to General Jackson’s troops, to the Jaguars.

But the Jackson-only option doesn’t sit well with Rodriguez and some other residents pushing for a name change. They said that still honors Stonewall Jackson, especially given its location on Stonewall Jackson Road. A spokeswoman for the city said it has received no requests to change the street name.

Johanna Lopez, the Orange County School Board member in whose district the middle school sits, said she’s heard from a number of constituents who want a completely new name.

“They feel very upset,” Lopez said. “They don’t feel comfortable with the name, and they don’t feel comfortable with the process.”

School board policy says that in renaming a school, the superintendent is to present two options to the school board, the current name and a new one. Typically, the new suggestion is one recommended by the school advisory council.

But Lopez questioned whether the shortened Jackson Middle could even count as a new name and noted the school board, though it considers community views, has final say on school names. She expects the Stonewall Jackson issue to be taken up in January or February.

The school advisory council surveyed the community twice about the Stonewall Jackson name. The first survey in 2018 asked respondents if they wanted to get rid of the name, and nearly 47% said yes, 43.5% said no and about 10% had no opinion.

About 2,000 people filled out that survey. Of those who wanted a new name, 54% said no to using just Jackson.

A second survey, done earlier this year, offered five different name options, one of them Jackson Middle School. The others were Engelwood, Journey, La Costa or Semoran middle schools, most of which referenced places in the neighborhood.

Jackson got about 64% of the votes, but far fewer people — 824 — took that second survey.

Lopez, a longtime Spanish teacher at nearby Colonial High School, is the first Latina and the first person from Puerto Rico elected to the Orange school board. She said she wasn’t sure whether those who filled out the survey, 65% of them students, understood the name’s history.

“The community was not informed or educated on who was Stonewall Jackson,” she said.

“They feel very upset. They don’t feel comfortable with the name, and they don’t feel comfortable with the process.” — Johanna Lopez, an Orange County School Board member

Historians say white-run school boards in the South gave schools Confederate leader names starting in the mid-1950s as a way to express displeasure with the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision striking down school segregation. A 1964 Orlando Sentinel story showed the school board also considered naming the school after Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy.

Jackson was a Virginian who died after a Civil War battle in that state in 1863.

Rolando Sanz-Guerrero, the advisory council’s chairman, said after the council’s October vote that those who wanted the Jackson name minus Stonewall — they won 10- 3 — viewed it as a generic choice without ties to the Southern Civil War leader. It would formalize what many already called the school and avoid the expense of redoing sports uniforms, school stationery and the like, Sanz-Guerrero said.

But since then others have voiced opposition.

“The Confederacy is dead. That name is dead.” — Jose Rodriguez, who attended the school in the 1990s

“It’s just appalling. A Band-Aid approach to just take the first name off the name, as if Jackson wasn’t connected to the name,” said Marcos Vilar, executive director of Alianza for Progress, a group working to boost Puerto Rican and Latino involvement in civic issues. “That’s a copout.”

He would like the school board to consider naming the school after a notable Hispanic as none of the Orange school district’s 200 campuses have such a moniker.

“We’re going to continue to push the school board to make the right decision,” Vilar added.

Rodriguez said he’s convinced a full name change for the school is inevitable, even if it doesn’t happen in the coming year.

“The Confederacy is dead,” he said. “That name is dead.”